MORE LESSONS LEARNED ABOUT PANDEMIC RISK

UNDERSTANDING VIRAL LOAD, METHODS MEASURING IT, AND DIRECT AND INDIRECT TRANSMISSION FROM SRA RISK PRACTITIONERS

https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/coronavirus-resource-center

Before I introduce you to the fascinating perspectives of 3 more Society for Risk Analysis (SRA) risk practitioners in the COVID Conversations on Risk series, here are reminders about microbial dose-response principles explaining why viral load (estimated inhaled dose) is crucially important for recovering from the pandemic.

The higher the initial dose,

the quicker you’ll get ill (shorter incubation period)

the more likely you’ll get ill

the more likely you’ll become severely ill if you have one or multiple co-morbidities

the longer you’re likely infective to others (longer duration of viral shedding)

Also, if your medical professionals are measuring your initial viral load, they’ll have more information about how quickly you might need specialized care to stop viral replication and prevent uncontrolled inflammation in your lungs. However, the available evidence for modeling outcome from viral load over time in different clinical samples (saliva, nasal or throat swabs, blood, urine, feces) by the most commonly used method (RT-PCR) are fragmented, represent very small numbers of cases that may not be representative of future cases, and may be reported as qualitative (positive or negative), semi-quantitative (high, medium or low categories), or quantitative (e.g., numbers of viral copies per mL of sample or per sample) of different utility for risk assessment. For microbial risk assessors to develop predictive models to assist in communication and management of pandemic risks, higher quality data is needed for reliable dose-response assessment.

I hear many frustrations voiced about all the uncertainties around this pandemic. Here are some grave frustrations for the global community.

This SARS-CoV-2 virus seems to replicate to higher levels early in the course of mild disease (e.g., at symptom onset) compared to related viruses that peaked a week or more after onset of symptoms severe enough to require medical intervention. The later peak likely provided some measure of protection limiting transmission for other viruses. Higher viral loads in people just starting to develop symptoms may contribute to higher rates of transmission and infection if social distancing and masking requirements are relaxed.

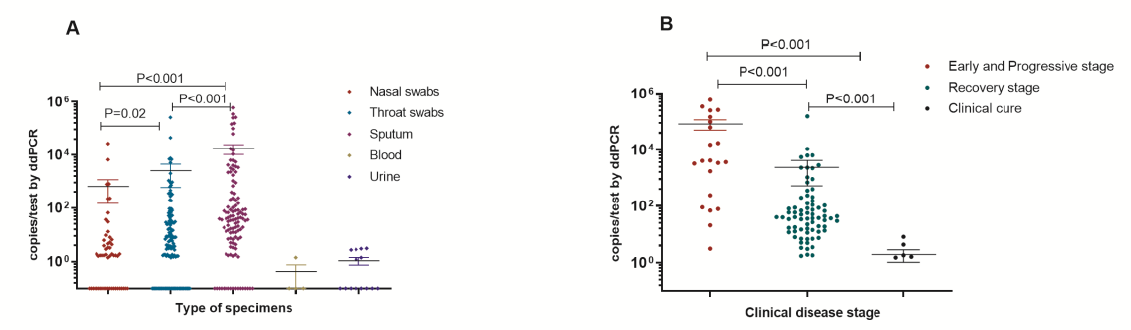

People who test negative at one point in time for viral RNA in upper respiratory tract swab samples may be infected, but the most commonly used methodology (RT-PCR) cannot ensure absence of the virus in the body, particularly in the lower respiratory tract, the primary site of viral damage. One recent study (Wyllie et al., 2020) reported that their RT-PCR method would not detect less than 5,610 viral copies per mL sample fluid (<16,830 viral copies per 3-mL homogeneous sample volume). Two more recent studies reported on higher sensitivity methods using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), one reportedly 500 times more sensitive (Suo et al., 2020), the other reported detecting from 10 to a million viral copies per test (Yu et al., 2020; see Figures from this study below). A third study (Patrone et al., 2020) reported improvements in sensitivity of RT-PCR by baseline corrections. Note that in addition to poor method sensitivity at low viral loads, false negatives could also reflect inconsistencies in swabbing efficiency or other sampling errors.

Resources (time, expertise, costs of kits and reagents) are limited for testing huge populations around the world, and repeat testing limitations during recovery before discharge are likely to be just as critical as getting the initial round of testing completed in stopping the pandemic.

To illustrate the importance of using sensitive methods for quantitating viral load, figures from the Yu study below (Figures 3A, B, E) represent viral loads in 95 samples collected over time from 76 patients admitted to a Beijing hospital prior to February 19th. Samples were analyzed by the more sensitive ddPCR method. Chart A illustrates significantly higher viral loads in sputum compared to other types of samples (nasal and throat swabs, blood and urine). Chart B illustrates significant decline of viral load in sputum at three stages of disease progression. Chart E illustrates two special cases in convalescing patients with low level fluctuations in viral load from 10 to 150 viral copies per test for 9 days in the recovery stage before testing negative. Variability in duration of shedding and viral load may contribute to further transmission of the pandemic.

SRA COVID Conversations on Risk Series

I highly recommend two more podcasts from the SRA COVID Conversations on Risk series. The first is a 30-minute audio interview of Dr. Vicki Bier of University of Wisconsin by SRA President Seth Guikema. Dr. Bier is a Professor of Industrial and Systems Engineering and is recognized as an SRA Fellow and recipient of many awards, including the Distinguished Achievement Award and the Richard J. Burk Outstanding Service Award.

Professor Bier described lessons learned from previous pandemics and cautioned that people need to continue practicing social distancing as restrictions are relaxing. A concerning example for this pandemic was from the H1N1 pandemic. Although 65% of subway riders in Mexico City initially complied with advice from authorities to wear masks, ten days later only 10% of riders wore masks. Another lesson learned from the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic is that the consequences of relaxing restrictions too early are high, with greater economic and public health damages in Denver during the second peaks of illnesses and mortality.

So, the WHO advice (DoTheFive) is just as important to follow now that some local communities appear to be past the (first) peak. Protect yourself and others by wearing a mask so that together we prevent that second peak from happening in our communities.

Two more exceptional panelists offered their perspectives on Food Safety and Food Security in the pandemic, Drs. Jade Mitchell and Felicia Wu.

Dr. Mitchell is Assistant Professor of Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering at Michigan State University and currently serves as Chair of the SRA Microbial Risk Analysis Specialty Group.

Dr. Wu is John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor of Food Science and Human Nutrition and Professor of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics, also at Michigan State University. Professor Wu serves as the Area Editor of Health Risk Assessment for the SRA journal Risk Analysis, and has received numerous awards including SRA’s Chauncey Starr Distinguished Young Risk Analyst Award, and was selected (twice) as Society for Risk Analysis/Sigma Xi Distinguished Lecturer.

View the podcast of the hour-long webinar at the link below.

Food Safety Highlights

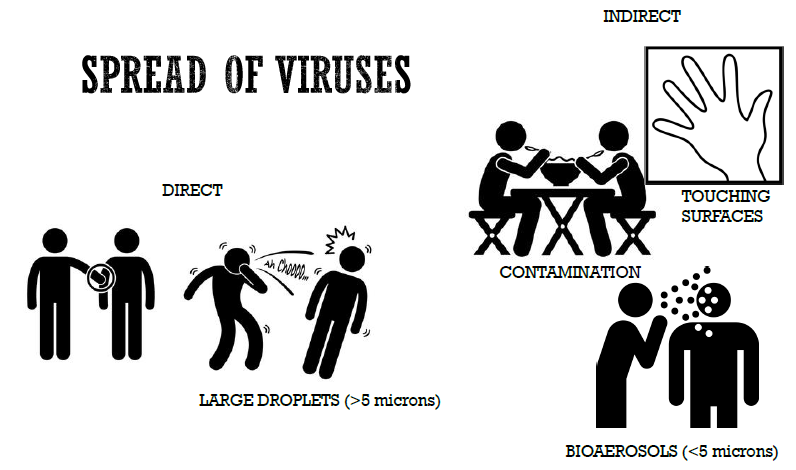

Fellow microbial risk assessor Dr. Mitchell illustrated how viruses spread by direct and indirect routes in this slide.

Dr. Mitchell also points out uncertainties about likelihood of transmission, notably that successful transmission depends on the dose inhaled being large enough to establish infection. No evidence exists, to our knowledge, documenting transmission and infection for SARS-CoV-2 that is attributable to contaminated surfaces. Rather, evidence points to direct person-to-person transmission via droplets (>5 microns) or bioaerosols (<5 microns) as most likely to transfer infective doses to others.

Transmission by asymptomatic cases is theoretically possible, but not documented as a contributing path so far in this pandemic. Most cases are clustered as typical for person-to-person transmission from droplets or aerosols in the vicinity of ill people in families and households, workplaces, and community gatherings where social distancing controls have been lax.

Indirect transmission from contaminated surfaces is theoretically possible, but not documented as a contributing path so far in this pandemic.

Indirect transmission from stool positive for viral RNA is theoretically possible (fecal-oral route), but not documented as a contributing path so far in this pandemic.

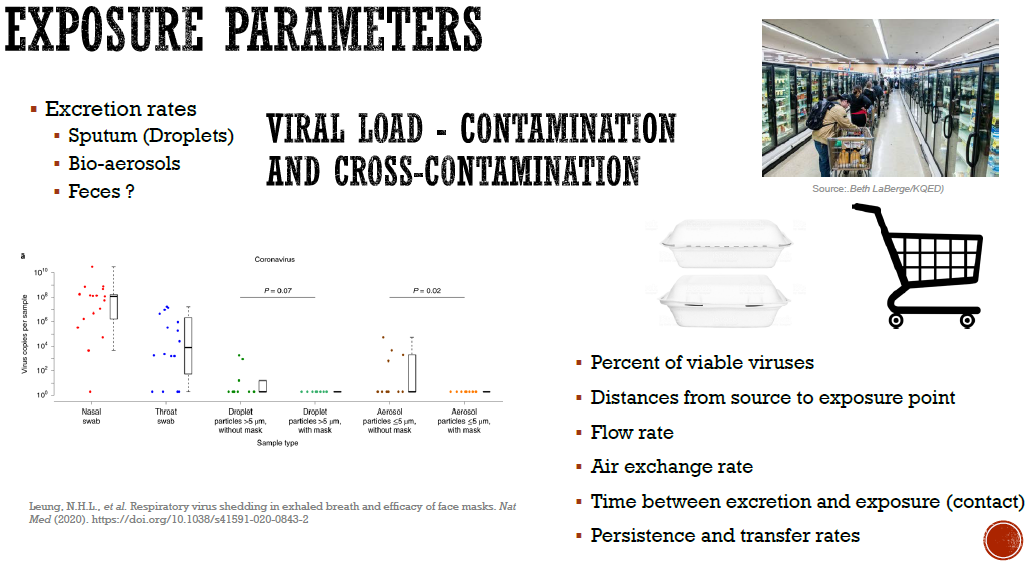

Another slide from Dr. Mitchell discussed exposure parameters influencing estimates of risk, notably viral load. The figure from the study that Dr. Mitchell cites (Leung et al., 2020) merits a closer look.

The level of viral contamination in nasal and throat swabs from 17 symptomatic confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 ranged from undetectable to 10,000,000,000 viral copies per sample. The researchers also measured viral shedding in exhaled breath from 10 cases not wearing a face mask and 11 cases wearing face masks. Breath samples were collected within 72 hours of onset of illness. For this small study early in the course of disease, low viral loads were detected by RT-PCR after 30 minutes monitoring breath of 3 or 4 of 10 cases not wearing masks, and notably virus transmission was not detected for 11 cases wearing masks. Clearly, masks reduce exposures to symptomatic cases.

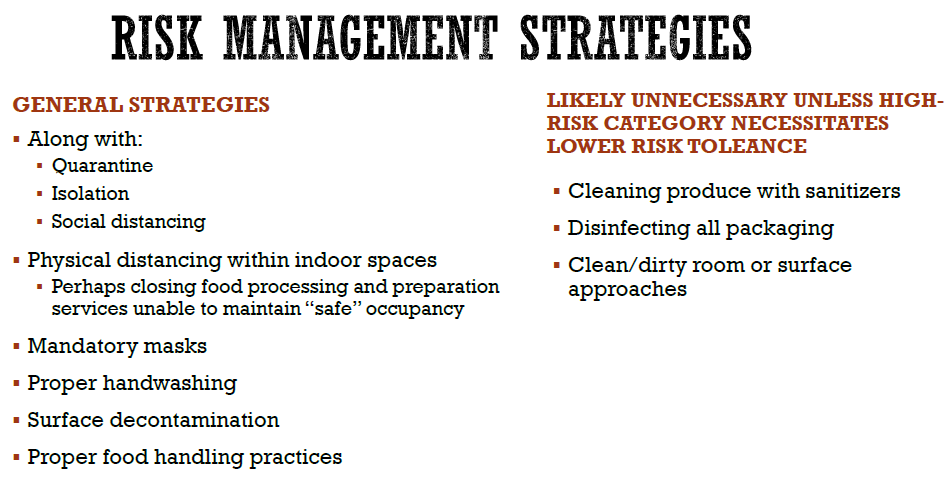

Dr. Mitchell closed with this slide conveying risk management strategies that are necessary (general strategies including social distancing) and some strategies (disinfecting food, packaging and rooms) that are likely unnecessary except for high risk groups.

Food Security Highlights

Professor Wu offered deep insights on food security and the complexities of determining a ‘social optimum’ for the appropriate level of system shutdown to balance public health and economic risks in this pandemic. Examples included health and economic risks to workers in production, processing, distribution, retail grocery, and restaurant sectors. Professor Wu discussed protests around what constitutes essential businesses. The pandemic has dramatically shifted focus on the most basic of needs from Maslow’s hierarchy, physiological needs, as illustrated in the screen shot below.

Further, Professor Wu described collaborative work (The Razor’s Edge of “Essential” Labor in Agriculture) submitted for publication in the journal Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. Certainly, food is “essential” for life on this earth, and Professor Wu provided insights on risks to workers throughout the farm-to-fork supply chains now disrupted at frequency and scale previously unimagined. Actions to work around disruptions are being put in place, such as re-distributing foods such as shell eggs and onions contracted by restaurants to grocery stores and food banks.

Can we keep the food supply robust during this pandemic? Professor Wu offers potential solutions, near-term and long-term, to design resilient systems for food safety and security. A number of potential solutions highlighted by Professor Wu include sustained use of drive-through curbside pick-up and delivery options from grocery markets and restaurants, to hope for near term and long term solutions that stop the pandemic and optimize the balance during recovery between enhancing public heath and minimizing economic risks.

Food Safety and Security Questions

The webinar audience posed many insightful questions, including one posed by my readers after my first blog. Why is an obligate viral pathogen that cannot replicate in the environment outside a host cell such a concern for society as local communities begin to consider relaxing social distancing restrictions? The responses returned to uncertainties about direct and indirect transmission routes.

The more likely transmission route seems to be direct inhalation of droplets and bioaerosols released in close environments from unmasked, convalescent, and early stage cases that bear high viral loads. While it is theoretically possible that indirect transmission of viral loads high enough to cause illness occur via transfer from contaminated (and unsanitized) surfaces via hands to face, it is unclear that sufficient viral particles exhaled by unmasked, convalescent, and undetected early stage cases that dry out from deposited droplets are transmitted to cause pandemic disease.

While scientific data is presently lacking to inform assessment of the likelihood and magnitude of risk for indirect transmission via contaminated surfaces in public buildings, transmission to care givers treating severe cases is well documented. The extensive transmission to workers who cannot DoTheFive, including poorly protected workers in meat processing plants, grocery stores, restaurants and other businesses, could be due to direct person-to-person transmission and not via indirect transmission from bioaerosols or dried virus deposited on surfaces. More research is needed before ‘natural experiments’ are observed where relaxing restrictions results in second peaks of illness and death.

Each risk practitioner featured in SRA COVID Conversations on Risk has reflected upon some silver linings, their hopes for enhancing safety and security of interconnected agricultural, economic, public health, and social systems as the pandemic subsides. More flexible and resilient systems offer future benefits to better balance priorities for public health, agriculture, economics, and social justice post-pandemic. As the world’s leading authority on risk science and its applications, SRA offers unique multi-/trans-disciplinary expertise and rigorous analytical perspective essential to synergistic teams who can effectively assess, communicate, and manage global risks incorporating uncertainty, ambiguity as knowledge advances, and complexities of our interdependent systems.

Local Community Responses

I am quite fortunate to live in beautiful rural upstate NY, in Tompkins County near Ithaca, where social distancing has been effective in limiting numbers of cases (129) and deaths (2) associated with the pandemic. The sobering statistics for other NY state counties are available on NYS-COVID19-Tracker and from NY City Health. Data by zip code is available from the latter site, as illustrated in the map below with cases as of May 6.

I am also fortunate to have compassionate and courageous neighbors, including Katrina who, along with her medical colleagues from Cayuga Medical Center and others, agreed to take a month of time away from our rural county to serve in Manhattan where 2,654 fatalities have occurred to date. NY State residents have suffered greatly, and most of the 19,415 deaths to date were reported in NY City, Long Island, and neighboring communities. Thankfully, no deaths were reported in persons under the age of 19 in this state. The sobering reality is that 84.4% of these deaths occurred in persons over age 60.

I cannot express in words how grateful I am that so many people around the world are battling COVID-19. Special thanks to Michele, a colleague and friend from Syracuse University, and others who have made fabric masks for family and friends. Insights on disruptions for workers are offered by another colleague at SU, Professor Ken Walsleben.

Although many communities are contemplating how and when to relax restrictions, the WHO message DoTheFive is crucially important to continue following. Let’s prevent the second wave and continue practicing social distancing for the greater social good.

Stay tuned for future episodes SRA COVID Conversations on Risk.